Research plan (detailed)

Contents

Research plan (detailed)#

NIHR134326: Stroke Audit Machine Learning (SAMueL-2)

Note: This is a follow-on project to a NIHR HS&DR project (Ref: 17/99/89), referred to here as SAMueL-1. An online book for SAMueL-1 (which includes both summaries and details of work) is available at: https://samuel-book.github.io/samuel-1

(This is Research Plan V3, 20/12/2021)

Summary of research#

BACKGROUND AND OVERALL AIM

In England and Wales, 11%-12% of emergency stroke patients receive thrombolysis, significantly below the NHS Long Term Plan target of 20% by 2025.

The overall aim of SAMUeL-2 is to work with the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) to increase the impact of national audit by providing advanced tools for in-depth comparisons between hospitals, helping to address the gap between actual and achievable thrombolysis use.

In previous work (SAMueL-1) we have used clinical pathway simulation and machine learning to model stroke pathways to thrombolysis at all (anonymised) hospitals, and to compare decision-making between hospitals. We found that about half of the current inter-hospital variation in thrombolysis use comes from differences in local patient populations and the other half from differences in hospital processes and decision-making. We found that stroke thrombolysis use could be reasonably expected to reach 18%-19% of hospitalised stroke patients. The largest single improvement would come from clinical decision-making at all hospitals being similar to 30 top- ‘benchmark’ hospitals with higher thrombolysis use. The next largest improvement would come from increasing the proportion of stroke patients whose stroke onset time is determined, to a level currently achieved by hospitals achieving upper quartile performance. Finally, speeding the stroke pathway at all hospitals would increase thrombolysis use, but by the smallest margin - although speeding the stroke pathway increases the clinical benefit of thrombolysis for all treated patients.

SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

Specific objectives are based on feedback received during SAMueL-1, and feedback on the SAMueL-2 bid proposal.

Expansion of SAMueL-1 modelling to include: 1) outcome and adverse event prediction at patient-level, 2) inclusion of pre-hospital times in pathway model, 3) use of organisational factors (such as staffing) in predicting use of thrombolysis, and 4) piloting of a model that incorporates use of thrombectomy alongside thrombolysis.

Incorporation of health economic outcomes (Quality Adjusted Life Years): These will be adapted from other NIHR projects involving this team that have already developed health economic models for thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke.

Promote acceptance of the modelling by increased transparency and explainability: 1) make use of Shapley values to show the contribution of individual features to the prediction that the model is making, 2) improved methods for clustering of patients to clarify patterns of differences in clinical decision-making between hospitals and to allow identification of ‘similar hospitals’ (by patient population) for comparison, 3) investigation of bias in model (e.g. accuracy analysis by patient subgroups), 4) generation of dashboards and other interrogative methods.

Generation of synthetic data and artificial patient vignettes: 1) build on pilot work already performed for generating synthetic patient-level stroke data that may be shared freely and used for discussion of ’virtual’ patients, 2) automatic generation of artificial clinical vignettes from real or synthetic SSNAP data.

Co-production of project outputs with clinicians to promote acceptance and use for local quality improvement: By using both information gathering (through interviews) and intervention refinement (in workshops) we will incrementally modify and improve the content and style of our intervention (SAMueL tool). Working with our Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) group we will also produce key public-facing output.

Background and rationale#

Stroke#

Stroke happens when blood flow to an area of the brain has been interrupted, causing cell death [1]. Stroke may be ischaemic, due to an arterial blockage, or haemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Stroke is the main cause of adult-onset long-term disability and a major burden on health and social care services. It was estimated that in 2010, there were 5.9 million deaths and 33 million stroke survivors worldwide [2]. Eighty-five thousand people are hospitalised with stroke each year in England, Wales and Northern Ireland [3]. Over the last 25 years in England stroke has consistently been one of the leading cause of lost disability-adjusted life years, which combine mortality and disability burdens [4].

Intravenous thrombolysis#

Intravenous thrombolysis is a ‘clot-busting’ therapy developed to treat ischaemic stroke by removing or reducing the blood clot obstructing blood flow in the brain. For ischaemic stroke, thrombolysis is an effective but time-critical treatment for the management of acute stroke if given within four and a half hours of stroke onset [5], and is recommended for use in expert guidelines worldwide [6].

Targets for thrombolysis use and speed#

The European Stroke Organisation have promoted a European Stroke Action Plan [7], including a target of at least 15% thrombolysis, with median onset-to-treatment times of <120 minutes, noting that evidence suggests that achieving these targets may be aided by centralisation of stroke services [8,9]. An analysis of the largest randomised trial of thrombolysis concluded that 60% of ischaemic stroke patients arriving within 4 hours of known stroke onset were suitable for thrombolysis [10]. In 2016-18 in England and Wales, about 40% of emergency stroke patients arrived within 4 hours of known stroke onset (data from SAMueL-1). Given that about 85% is stroke is ischaemic, this gives a potential target of 20% thrombolysis.

The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan [11] sets out the ambition of 20% of emergency stroke patients receiving thrombolysis, such that by 2025 England will have amongst the best performance in Europe for delivering thrombolysis. This target is incorporated into the 2021 service specification for the 20 new Integrated Stroke Delivery Networks [12]. Current thrombolysis use in England and Wales is 11-12% on average but ranges from about 2% to 25% between hospitals [3], and has been static at this level for the last 8 years.

The NHS plan for improving stroke care also sets a target that patients should receive thrombolysis within 60 minutes of arrival, but ideally within 20 minutes [12]. Whilst this speed of thrombolysis, called door-to-needle time, provides an ambitious target, it has been shown to be achievable as Helsinki University Central Hospital has reported a median door-to-needle time of 20 minutes, with 94% of patients treated within 60 minutes [13] - a model that has proved rapidly transferable elsewhere [14]. This speed was achieved by innovative solutions like paramedics taking patients straight to the scanner and with thrombolysis delivered close to or in the scanner.

Clinical audit#

Clinical audit seeks to drive quality improvement through the measurement of clinical quality against evidence-based standards [15]. In England and Wales, the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) is responsible for commissioning 28 national clinical audits which form the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme. The national audit of stroke is the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP), which collects data on the processes and outcomes of stroke care up to 6 months post-stroke for more than 90% of acute stroke admissions to hospitals in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Every year data from approximately 85,000 patients are collected. SSNAP publishes quarterly and yearly analysis of results on its website [16].

Clinical audit#

Foy et al. [17] recently revisited the case for national audits being effective and how they may be improved. Audit and feedback have been found to improve care, for example by showing individuals or providers that they are outliers, but it is important that recipients of the feedback are convinced by the audit, see it as specific to them and that audit promotes improvement action beyond simply measurement. A barrier to accepting feedback is the belief (true or otherwise) that “my patients are different”. Also, persistent negative feedback can lead to disconnection from the process of quality improvement. Foy calls for more intelligent use of audit with the call.

“Audit and feedback are widely used, sometimes abused, and often under-realised in healthcare. More imaginative design and responses are overdue; these require evidence-informed conversations between clinicians, patients, and academic communities. It is time to fully leverage national audits to accelerate data guided improvement and reduce unwarranted variations in healthcare. The status quo is no longer ethical.” Foy et al. 2020.

We respond to this challenge by using state-of-the-art modelling and machine learning tools that:

Are co-produced with clinicians to maximise perceived usefulness and minimise perceived threat.

Allow for differences in hospital patient populations (no ‘one target fits all’ approach).

Are patient-centred – focussing on outcomes as well as thrombolysis use. We will also identify types of patients where decision-making differs between hospitals, exemplified by artificial patient vignettes.

Are comprehendible by clinicians to build acceptance/validity.

Are action-focussed – identifying the actions to prioritise that will make most difference.

We are encouraged by discussions we have had on outputs from our previous work with several of the new Integrated Stroke Delivery Networks (ISDNs). Our existing work has stimulated significant interest already, particularly in the bespoke nature of the analysis and feedback. This encourages us regarding positive engagement with these improvement networks, especially regarding support with involving sites and/or clinicians that might otherwise be reluctant to engage or are sceptical about nationally-dictated ‘top down’ or ‘one size fits all’ targets.

Summary of SAMueL-1#

We built clinical pathway simulation models, and clinical decision-making models, based on patient-level data from SSNAP. We built machine learning models that would closely replicate the clinical decisions made at each hospital, predicting if a patient who arrived within the treatment window would receive thrombolysis. The decision models are based on clinical pathway timings and patient clinical features recorded in SSNAP, such as age, components of the stroke severity scale (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NIHSS), co-morbidities such as atrial fibrillation etc. The clinical decision-making models allow us to ask the counter-factual question, “What treatment would my patient be likely to receive at other hospitals?”. The clinical pathway simulation models predicted each hospital’s thrombolysis rate with an average absolute error of less than 0.5 percentage points. The clinical decision-making models predicted clinical decisions with 85% accuracy (achieving 84% sensitivity and specificity simultaneously) for those patients arriving within 4 hours of known stroke onset, with neural networks or random forest models having the highest accuracy.

Using our models, we found that about half of the current inter-hospital variation in thrombolysis is accounted for by differences in local patient populations. Most of the remaining inter-hospital differences were attributable to differences in clinical decision-making and, to a lesser extent, difference in hospital processes such as door-to-needle time.

We then tested three alternative scenarios at each hospital: 1) What if door-to-needle time was 30 minutes?, 2) What if all hospitals determined stroke onset time at least as frequently as the current upper quartile of hospitals?, 3) What if clinical decisions were made according to the majority vote of 30 top ‘benchmark’ hospitals? These benchmark hospitals are the 30 acutely-admitting stroke units with highest predicted users of thrombolysis using a standard set of 10,000 patients passed through all hospital decision models. The infographic below summarises our modelling findings. We found that making these changes at all hospitals would increase the national average thrombolysis rate to 18-19% (range 6-27%). The change that would have most impact would be alignment of clinical decision-making with hospitals more enthusiastic in their use of thrombolysis, then through better ascertainment of stroke onset times, and finally through speeding internal processes - although reducing door-to-needle time has a larger effect on overall clinical benefit, as they will benefit all patients who receive thrombolysis. For every additional 10 patients treated under these scenarios the primary reason was: clinical decision making in 5, determining stroke onset time in 4, and door-to-needle time in 1. The modelling produces a bespoke breakdown for each hospital, giving the realistic and achievable thrombolysis rate, and the impact of each component - helping to identify at each hospital which change would make the greatest difference to outcomes for their own local population. This is an important finding as prior to this, most improvement effort in thrombolysis has been based on the generalised assumption that the largest improvements in thrombolysis rate come from reductions in door-to-needle time [13].

Figure 1 below shows a summary of findings from SAMueL-1.

Fig. 1 A summary of findings from SAMueL-1.#

Previous qualitative research#

During SAMueL-1 we held physician workshops and conducted semi-structured interviews with groups and individuals. We found attitudes to our clinical pathway simulation and machine learning were related to whether the physician came from a hospital with either a higher or lower use of thrombolysis.

Doctors from hospitals with higher thrombolysis use: Were interested in the modelling and what it might mean for their own local circumstances.

Could see where it might help and identify how thrombolysis could be improved.

Wanted to know more about how changes might affect adverse events and outcomes.

Came from a hospital where there had been more effort/investment in the stroke pathway.

Doctors from hospitals with lower thrombolysis use:

Were interested in the modelling and what it might mean for their own local circumstances, but were more cautious or sceptical.

Wanted to provide best care, but worked in hospitals where there had been less work on, or investment in, the stroke pathway (e.g. fewer doctors, no specialist stroke nurses, poorer access to imaging).

Tended to think their patients were different (e.g. they arrived later, had more complex needs, were not classic/typical stroke).

Were concerned that increased use of thrombolysis would cause more harm than good.

SAMueL-2 aims and objectives#

The primary aims of the project are:

1.To maximise the impact of national comparative audit on clinical practice change in thrombolysis through the development and use of sophisticated hospital-level analysis and bespoke feedback. This analysis, allowing for differences in hospital patient populations, will investigate both the benefit and potential harms of thrombolysis. Hospitals will be compared with both national benchmarks and with a group of hospitals with similar patient populations.

To evaluate the potential health economic impact of realistic and achievable alterations to the acute stroke care pathway.

Using co-production with clinicians, determine the best way to use and present the outputs from SAMueL-2 to increase impact and reduce unwarranted variation in clinical practice in thrombolysis.

Based on clinician feedback received during SAMueL-1, and feedback received during first stage review, the specific objectives of this project are as follows:

Machine learning and clinical pathway simulation#

We will build significantly on the machine learning of SAMueL-1:

Outcomes: Include prediction of clinical outcomes at 24 hours after thrombolysis, discharge, and 6 months in machine learning, and prediction of thrombolysis-related haemorrhage. This objective is to address concerns that using higher-thrombolysing hospitals as the benchmark may drive thrombolysis use that may cause more harm than good.

Organisation factors: Include factors from SSNAP organisational audit into our machine learning model predicting thrombolysis use and outcome. This objective addresses questions of whether there are key organisational factors are associated with higher thrombolysis use.

Ambulance response: Include ambulance response times in clinical pathway simulation. This objective addresses the observation from SSNAP that in recent years improvements in door-to-needle time have been cancelled out by lengthening pre-hospital onset-to-arrival times [18].

Thrombectomy: Extend the application of this approach to thrombectomy (endovascular treatment of stroke). This extension will apply to both the clinical pathway simulation model and the machine learning models. This objective responds to the developing landscape of stroke treatment. Thrombectomy numbers in the UK are likely to remain too limited for robust analysis through machine learning, but we will pilot an extension that may include use of thrombectomy as well as thrombolysis.

Incorporate Health Economic models#

This project shares investigators with the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research PEARS (Promoting Effective And Rapid Stroke care) and OPTIMIST (OPTimising IMplementation of Ischaemic Stroke Thrombectomy). These projects have implemented, or are implementing, health economic modelling for use and speed of thrombolysis and thrombectomy. In this project we will incorporate and adapt health economic methods developed by these other NIHR projects and apply them in our modelling.

Improve intelligibility and trust in modelling and machine learning#

Implement Shapley values, a recently developed method that may be used in all machine learning model types, to explain the contribution of individual features to predictions the model is making. This responds to a lack of trust from some clinicians in the concept of predictive modelling. We will allow them to see how the model is making predictions and which factors influence the model prediction more towards or away from giving thrombolysis.

Improve methods for patient clustering, such as by using decision-tree distance in random forests, or embedding distance in neural networks. This will more easily identify groups of similar patients where clinical decision-making varies between hospitals, and identify typical patients in each group. Being able to measure similarity between patients (and hence patient populations) will also allow us to find hospitals with similar patient populations for use as peer comparators.

Generate dashboards and other methods for model interrogation to augment the key statistics. This seeks to make the models more transparent and understandable, and hence increase acceptance and gain traction. We will produce pilot dashboards in a streamlit.io framework (currently being adopted by SNAP) that may be adopted and/or refined by SSNAP and may inform initiatives in other national audits.

Investigate bias in the model. We will analyse two types of bias: 1) Bias that reflects real-world bias such as differences in hospital decision-making regarding whether patients with pre-stroke disability should receive thrombolysis, and 2) bias in the model whereby model accuracy is not equal for all subgroups.

Create synthetic data and patient vignettes#

Synthetic data allows people to explore a machine learning model in more detail with large cohorts of representative data, and is therefore beneficial to the open exploration of issues and uncertainties, and to open science (our synthetic datasets will be published so that allow other groups to apply novel methods and tools to address this pro). Patient vignettes may be used to provoke discussion between clinicians on when to use thrombolysis. We will extend our work in two areas:

Generation of synthetic patient-level stroke data. This data will resemble raw SSNAP data.

Generation of synthetic patient vignettes which convert SSNAP-like data into a clinical vignette for discussion. We piloted this approach in the first project and found clinicians engaged with these well.

Explore how best to incorporate modelling and machine learning into local improvement#

We will carry out qualitative work to answer the question “Given existing variations in thrombolysis use, what is the best way for us to use and present the outputs of machine learning to reduce unnecessary variation and promote best patient outcomes?” This work will form a vital bridge between clinicians (users) and the modelling team to ensure that the science translates to real world settings and practice.

We will recruit up to 40 clinicians from hospitals across the spectrum of thrombolysis use (ensuring we get good representation from those hospitals with lower thrombolysis rates) to a clinician panel that will be asked to provide feedback and critical comments via regular meetings and email contact throughout the project. Specific planned activities include:

Identify required improvement/refinements to the SAMueL-2 tool. We will hold co-production workshops with clinicians throughout the project to present the SAMueL-2 tool results and dashboards and gather feedback.

Gather feedback on synthetic patient vignettes. We will ask up to 20 of these clinicians to provide feedback on synthetic patient vignettes, and related material on differences in clinical decision-making, using think aloud interviews. This will help shape how this work is presented in order to maximize reflection on clinical decision-making around thrombolysis, which we have identified as the most significant modifiable source of inter-hospital variation in thrombolysis use.

Explore intelligibility and trust in modelling and machine learning. We will again use think aloud interviews with approximately 20 of these clinicians to explore intelligibility and trust in modelling and machine learning and to understand how the SAMuel-2 tool could address individual scepticism and organisational barriers to improving rates of thrombolysis.

In addition to these activities, we will work flexibly and responsively with this panel to explore specific implementation questions that emerge during the project, for example convening virtual meetings to examine how best to configure the dashboard, or to understand the kinds of health economics modelling they would find most useful. Qualitative data will comprise meeting notes, interview transcripts and workshop outputs which will primarily be analysed using a combination of thematic approaches and framework analysis.

Promoting Open Science#

We will continue to work using the principles of open science, as described by The Alan Turing Institute in The Turing Way (https://www.turing.ac.uk/research/research-projects/turing-way-handbook-reproducible-data-science). Using fully open code published in an online Jupyter Book like SAMueL-1, and using synthetic data, we hope this project will be useful as an example to others working with large publicly-funded datasets.

Research plan and methods#

Overall attribution of requested funding#

Leadership & management: £25,970; Modelling and health economics: £171,284; Qualitative (co-production): £134,726 (+ £8,640 NHS support costs); PPI: £5,665; Dissemination: £2,240; University overheads: £256,515.

Clinical pathway simulation and machine learning#

The key methodology of the project will be based on the methodologies employed in SAMueL-1, namely:

Clinical pathway simulation: Based on Monte-Carlo simulation using Python/NumPy. Prediction of probability of good outcome derived from a meta-analysis of clinical trials and is based on age group and time from onset to treatment [5].

Machine learning: predicting likelihood of receiving thrombolysis using patient and clinical features, time of stroke, time of arrival and scan, and hospital attended. Based on extensive testing in SAMueL-1, we will use random forests and neural networks. Use of these two contrasting machine learning methods will ensure the robustness of our results.

Clinical pathway simulation will be enhanced from SAMueL-1, in the following way:

Incorporation of ambulance response, travel, and on-scene times (now available in SSNAP), allowing for ‘what if?’ testing of scenarios that alter pre-hospital timings.

Machine learning will be very significantly enhanced from SAMueL-1 in the following ways:

Prediction of patient-level outcomes and risk of thrombolysis-related haemorrhage, based on data in SSNAP (24 hour NIHSS, modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at discharge, mRS at 6 months, label of thrombolysis-related haemorrhage). Note: mRS at 6 months is only partially complete, with just over 40% of those who survive to discharge having a recorded outcome at 6 months. We will test our ability to predict 6-month mRS (and therefore impute it when missing) using regression machine learning algorithms (e.g. random forests regression, neural network regression). A ‘fall-back’ strategy is to base outcome models just on 24 hour NIHSS, mRS at discharge, and thrombolysis-related haemorrhage.

Incorporation of organisational factors (such as staffing) for each hospital. This will come from the biennial SSNAP organisational audit being conducted in October 2021.

Building acceptance of, and trust in, modelling#

An important focus in SAMueL-2 will be building methods to demonstrate trustworthiness of the models. We will be guided by the FAT-ML Principles for Accountable Algorithms (https://www.fatml.org/resources/principles-for-accountable-algorithms):

Responsibility: Allow people to highlight issues with algorithms and have a mechanism to address them.

Explainability: Ensure that algorithmic decisions can be explained in non-technical terms.

Accuracy: Identify and communicate sources of error and uncertainty in the algorithms and the data used to train the algorithm.

Auditability: Allow others to probe, understand, and review the behaviour of the algorithms.

Fairness: Ensure that algorithmic decisions do not create discriminatory or unjust impacts when comparing across different demographics (e.g. race, sex, etc).

Conceptual model for decision-making#

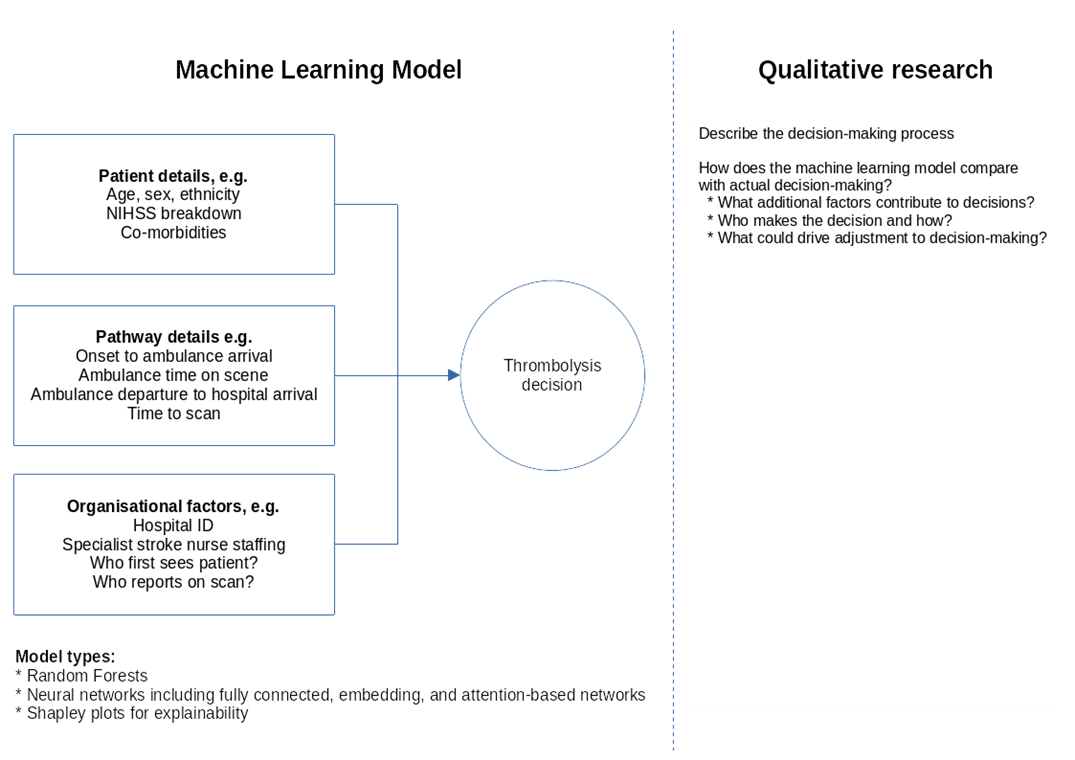

We will explore clinical decision-making in two ways: 1) A machine learning model, and 2) Qualitative research. An overall conceptual model is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2 Conceptual model of decision-making#

Machine learning models are necessary simplifications of real-world decision-making. This is especially true when applying these models to audit data as, though extensive data is available, we are limited to the data that has been collected and stored nationally. We do not expect the machine learning model to incorporate all aspects of clinical-decision making, but results from our previous project show that we can achieve an ROC-AUC of 92% and an overall accuracy of 86% for those patients arriving at hospital with time left to give thrombolysis. The model therefore encapsulates a lot of the information that drives decision-making (and the planned project will add some further information to the model inputs, so we may improve accuracy). These models reveal differences in decision-making such as attitudes to giving thrombolysis to milder strokes, to patients with pre-existing disability, or to patients with imprecise stroke onset times.

Including in our modelling are explanatory models showing what factors are most influential in the model, both overall and for individual patients. We know our models are ‘well calibrated’ – that is when the model has high certainty on whether a patient will receive thrombolysis or not, then it is almost always right. But when the model has low certainty then the accuracy of the model is worse. We will explore what the characteristics of the input that enable the model to be certain, and what are the input characteristics of the model when it is uncertain (we will also perform a similar analysis on looking at the characteristics of patients with predicted high variation in expected treatment between stroke teams).

Our qualitative research will add another layer to exploring decision-making, exploring the context of the decision-making – who is making the decision, and what the aspects of the decision-making that are not included in our machine learning model. This adds a ‘real world’ rich view on top of the machine-learning model, and through this work we will also explore how we might best influence decision-making.

Clustering of patients and identification of hospitals with similar patient populations#

Clustering of patients, using similarity metrics between patients, allows us to identify ‘typical’ patients that exemplify key differences in decision-making between hospitals. By generating similarity metrics between patients, we may also identify hospitals with similar patient populations. These may be used as comparator hospitals such as the ‘similar ten’ comparator groups used to compare Clinical Commissioning Group performance (https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/similar-10-ccg-explorer-tool/), avoiding the problem of comparing hospitals with dissimilar populations.

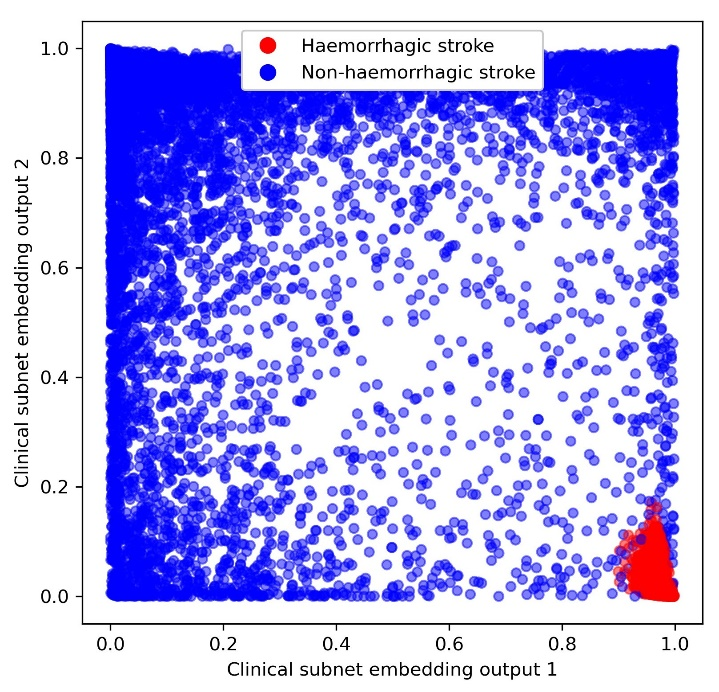

In SAMueL-1 we began this work, using both random forests (looking at distances between patient ‘leaves’ induced by the sequence of decisions used to classify them) and neural networks. An example of a novel approach to patient clustering, using neural networks, is shown below in Figure 3.

Fig. 3 Patient characteristic embedding, marking of those patients with a haemorrhagic stroke (red) as opposed to a non-haemorrhagic stroke (blue).#

We use embedding layers in a similar way to natural language models which encode words so that similar words (e.g. ‘big’ and ‘large’) end up close to each other in the encoded embedding space. The figure shows an example where the neural network encodes patients by similarity in decision-making, so that patients that appear similar when making decisions are located closely together. Using this approach, we find haemorrhagic patients closely clustered together (red cluster of patients in lower right of plot). Though not shown in this figure, we find other groups also closely located together elsewhere in the embedding space (e.g. patients who received thrombolysis, or patients who were not given thrombolysis but had very severe stroke). Expanding the number of embedding dimensions (here we use just 2 for simplicity) and using clustering techniques, such as k-means, should allow us to find types of patients that are typical of differences in decision-making between hospitals.

Synthetic patient-level data and vignettes#

Synthetic data#

In SAMueL-1 we piloted generation of synthetic patient-level data that could be used to train machine learning models [21]. Techniques included SMOTE, generative adversarial networks, variational auto-encoders, and sampling from principal component analysis distributions. We found that synthetic data could be used to train and exemplify machine learning models with minimal loss in accuracy. We will extend and use these methods (e.g. with additional random-forest based methods and with an additional differential privacy layer) to generate large data sets of synthetic patient level data that can be used by people examining the model, or used to discuss examples of differences in decision-making between hospitals without risk of breaching patient confidentiality. We will assess the quality of the generated data by implementing methods to measure both utility (how well do the statistical properties of the synthetic data match those of the real data) and disclosure (how much information does the synthetic data reveal about the real data). Specifically, we will use:

Cross-classification to measure the utility of the synthetic data. Cross-classification involves training a model on synthetic data and assessing its performance on real data. It is a method we have tested in SAMueL-1.

Random forest similarity to measure the disclosure of the synthetic data. Disclosure can be minimised by ensuring that no point in the synthetic data is too close to any point in the real data. Using the similarity metric developed in our previous work, for each point in the real data we will find the closest point in the synthetic data. If the distance between these points is less than a threshold value, the synthetic data point will be perturbed to increase their distance.

A differential privacy layer to add an extra layer of privacy2.

Vignettes#

Below is an example artificial patient vignette from SAMueL-1. This is based on key SSNAP data, with an imagined narrative that fits that data. Doctors have engaged well with these, which bring an additional human dimension to the raw data. In SAMueL-2 we plan to automate vignette generation by building up from a selection of appropriate blocks that match the SSNAP data.

Sally is a 76 year old woman with hypertension who had a TIA three years ago, who was taking clopidogrel, bendroflumethiazide and a statin. She found her knee arthritis a bit of a nuisance when shopping. She started to feel a slight weakness in her left arm and leg as she was making dinner for herself and her husband, Roy, one Thursday evening. She thought her knee was playing up and put the 6 O’Clock news on the radio to take her mind off it. However, when Sally and Roy sat down to eat at 7pm he noticed that she was clumsy with her fork and he thought her face looked twisted on the right. As she had previously had a TIA, Roy was alarmed and quickly dialled 999. An ambulance arrived within 10 minutes, and by 7:28 pm she was being assessed in the emergency department of her local hospital.

The first doctor to see Sally quickly sent her for a CT brain scan, which happened at 7:59pm. Once back in the emergency department, the doctor assessing Sally noted her history of hypertension and TIA but that she was otherwise generally well. The doctor noted a minor drooping of her face, and a drift of her left arm and leg which were also slightly numb, and it seemed to make her left arm rather clumsy. Her NIHSS was 5. The scan showed no signs of haemorrhage, but there was an old lacunar infarct in the left hemisphere. The doctor decided that the risks of thrombolysis outweighed her potential to benefit as she thought the natural prognosis from her mild stroke was good even without thrombolysis. She subsequently admitted her to the stroke unit for observation.

Implementation#

The code we generate will use all open Python libraries and, as with SAMueL-1, we will create a single Python file or Jupyter Notebook that will run all the standard analyses, off the back of a SQL query by SSNAP. We have worked with the SSNAP analytics team during SAMueL-1 on integration, and we will continue to work with them to ensure that our methodology and code is ready to implement following their upgrade to Microsoft Azure Database servers.

In order to enhance user-friendliness, SSNAP are currently reconfiguring their dashboards away from downloaded Excel sheets to interactive web pages using streamlit.io. We will similarly develop pilot output using streamlit.io that may be adopted or refined by SSNAP (streamlit.io is designed to be easily compatible with Jupyter Notebooks, which is the environment our project already uses for clinical pathway simulation and machine learning).

Health economic modelling#

Overview#

The health economic theme of SAMueL-2 is concerned with the short-term and long-term resource and health-related quality of life outcomes that are a consequence of differing levels and speeds of thrombolysis treatment. The analyses undertaken in SAMueL-2 will aim specifically at informing policy makers and commissioners of acute services about the health and resource consequences of differing levels of treatment.

Methodologies#

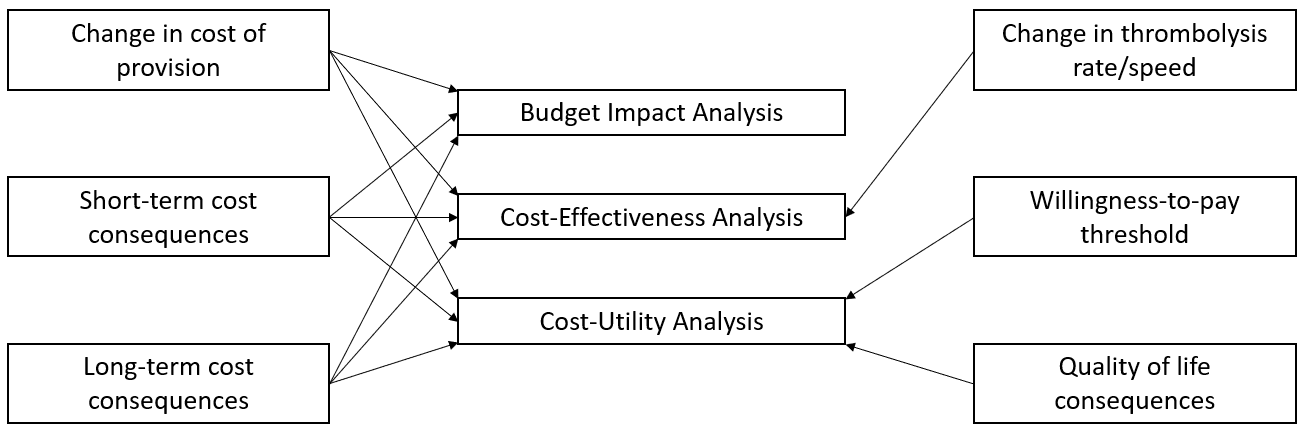

The health economics methods will comply with appropriate guidelines, notably the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force on Good Research Practices-Modelling [22]. Models developed will take an NHS perspective within an extra-welfareist framework [23]. Specifically, the resources included within the analyses will be those consumed by the NHS in prehospital, hospital and community care settings. Health quality of life will be quantified using an instrument to which national tariffs apply and, when appropriate, ‘willingness-to-pay’ for gains in health-related quality of life will be applied. Health economic outcomes will be expressed in terms of the marginal difference between the service levels being modelled and the most appropriate alternative. The three types of economic analyses that will be used (Budget Impact Analysis, Cost-Effective Analysis and Cost-Utility Analysis) are listed in Figure 4, together with their key summary inputs.

Fig. 4 Types of economic evaluation and their constituents.#

The economic analyses each report on a different facet of the consequences of different levels of service provision: 1) A Budget Impact Analysis is focused on the financial consequences (and is often reported in time-frames consistent with NHS budgetary cycles); 2) the cost-effectiveness analysis on efficiency of provision and, 3) the cost-utility analysis on the gains in health-related quality of life. Each analysis addresses different issues for policy makers. The estimation method used will be based on a Kaplan-Meier sample average type estimator. This method weights expected health-related quality of life and costs by the probability of survival.

The health economic analysis will use appropriate techniques to address the issue of uncertainty in estimates. Uncertainty is particularly relevant to economic models where data is drawn from different sources [24]. Appropriate sensitivity analyses will be carried out alongside estimation of overall uncertainty around the results of each analysis. Such sensitivity analysis may be informed, for an example, by comparison of the Northumbrian patient cohort with the national SSNAP data set obtained by the project for the machine learning and clinical pathway simulation modelling.

Data informing health economic analyses#

In the majority of health economic analyses, complete primary data is not available. Instead, data are frequently combined from several sources, including literature reviews and registries. The modelling for SAMueL-2 will rely on data gathered from a variety of sources. The process of building the health economic models will include a review of the most appropriate sources of evidence to include in the models as well as identifying what sensitivity analyses should be carried out. Evidence can either be short or long-term. Short term evidence includes data about the acute phase of care and is typically drawn from trials and registries, with care being taken to ensure data used is relevant to the NHS context.

The first long-term evidence used within the health economic models will be mortality. SAMueL-2 will use estimates based on mRS post stroke (recorded at hospital discharge and at 6 months). The techniques used will be the same as used in other longer term economic models such as the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, which used a Gompertz regression model for death following onset of type 2 diabetes [25]. In-hospital mortality and mortality within 30 days from admission will be obtained from SSNAP. Longer term mortality, in the form of conditional parametric survival functions, will be derived from a linked data-set of 2,000 stroke patients, followed up for an average of nine years (Northumbria Healthcare). As well as allowing an estimate to be made of the effects of increased treatment rates on mortality, these estimates will directly inform the economic analysis through their effect on health-related quality of life and resource use. As this data set is obtained from a single provider, sensitivity analysis will be undertaken to explore uncertainty of the derived parameters. This sensitivity analysis will be based on published life expectancy after stroke [26–28].

Health-related quality of life will also be modelled with a quality adjusted life year (QALY) framework. In this model, mortality and morbidity are combined to create the QALY [29]. In SAMueL-2 morbidity estimates will be come from utilities mapped to the mRS, although over the duration of SAMueL-2 an increasing amount of outcome data will accumulate using the EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L which was introduced into SSNAP in July 2021. Utilities are values scaled between zero and one that reflect health related quality of life, where one represents full health and zero represents death. The conditional probability of a QALY will be derived from post stroke mRS (or EQ-5D-5L), its associated utility score and probability of survival. For example, a recent study found utility values of 0.97, 0.88, 0.74, 0.55, 0.20, −0.19, and 0 for mRS scores of zero (no symptoms) to 6 (dead) respectively [30]. Utility values used in SAMueL-2 health economic models will be drawn from the literature following a literature search. A similar method will be used to estimate lifetime costs. Annual healthcare costs associated with different levels of the mRS will be weighted by the probability of survival. A review of published studies will be conducted to identify these costs. Longitudinal studies of costs are typically less common than cross sectional studies of costs or health related quality of life because of follow-up costs. In the case of non NHS sources, for example Dewilde and colleagues reported Belgian healthcare costs [31], a purchasing power parity conversion will be carried out to facilitate use across national boundaries [32]. In keeping with best practice, all future costs and QALYs will be discounted at an appropriate rate - currently 3.5% annually for costs and 1.5% for QALYs [33].

Qualitative research#

Research question#

Our research question is: “Given existing variations in thrombolysis use, what is the best way for us to use and present the outputs of machine learning to reduce unnecessary variation and promote best patient outcomes?” This will involve comparing our clinical decision-making model with clinicians description of clinical decision-making (who makes the decision and how?), and how to do we use the machine learning model to drive beneficial adjustments to clinical decision-making?

Qualitative research will work alongside the modelling work – enabling us to field-test and refine modelling outputs as they are produced. We will work with clinicians and others (e.g. commissioners) in order to co-produce a means of bringing about change in practice using our SAMueL-2 models. The goal of this co-production is to bring together our group’s machine learning and modelling knowledge with clinicians’ expertise and perceptions of what will improve the decision-making of themselves and their peers, so that the clinicians can help shape the outputs from the tool to be most constructively engaging.

Background#

From our group’s previous work in SAMueL-1 on variation in thrombolysis practice we know that clinicians’ perceptions of why they will not or cannot change their practice are influenced by practical and resource constraints and by concerns regarding risks. From other work on changing practice, we know, first, that changes in practice do not automatically or straightforwardly follow the existence, or even the awareness, of evidence [34]; second, that clinicians are not always consistent/methodical decision-makers [35,36]; and, third, that it is important to pay attention to the broader context in which clinicians work and consider “the historical, economic, professional, and social forces” [37] that influence their behaviour, including in relation to evidence-based practice in acute stroke care [38].

Across a range of clinical settings, the implementation of evidence-based practice is affected by multiple overlapping factors at system, organisational, department, and individual levels [39] as well as by differences in new and existing practices, practitioners, patients, and policies and by the interactions between these things [40]. Even decisions apparently based on individual clinical experience and judgement are situated within and shaped by organisational cultures [41] and by organisational climate and social context [42].

In light of this complexity, we need to consider how we can best use our SAMueL-2 models to reduce variation in the use of thrombolysis, and thus to improve patient care and outcomes. Another way of looking at this is as a double implementation problem in which we are concerned with: 1) the uneven implementation of thrombolysis [43], and 2) with preparing and presenting our model in a way that will make it the most acceptable and effective tool possible to support optimal implementation of thrombolysis.

Theoretical framework#

We will anchor our work in established theory and frameworks. Our theoretical approach is grounded in strong structuration, which has been used before to examine socio-technical aspects of healthcare IT implementation [44] as well as in organisational studies more broadly [45]. Giddens [46] proposed structuration as a way of moving beyond the sociological tension between structure and agency - that is, of resolving the argument over whether human actions produce social conditions or social conditions determine human actions - by recognising that the two things are mutually informing and that social conditions (structure) both shape and are shaped by human action (agency) such that the two things co-evolve. Giddens’ work was highly theoretical and abstract but from it Stones developed strong structuration theory [47], which he designed to be more empirically and epistemologically grounded in specific, situated social situations and practices [45].

We will encourage participants to draw on their own experiences, particularly in relation to evidence, evidence-based medicine, and individual clinical judgement within their professional and organisational context. We will shape our approach and analyses after the four questions described by Broom and colleagues [41].

What is the basis of a particular experience, action, belief, relationship or structure?

What do these assume implicitly or explicitly about particular subjects and relationships?

Of what larger process is this action/belief, etc. a part?

What are the implications of such actions/beliefs for particular actors/institutional forms?

Although audit and feedback is moderately effective as a means of improving quality of care, and leads to modest improvement in professional practice, there is substantial variation in the reported effects [48]. One proposed way to increase the effectiveness of audit and feedback is to construct feedback through social interaction, based on the observation that learning from feedback is better when people engage with it in a social situation rather than passively received [49]. Our combination of national comparative audit data with machine learning-informed case studies/vignettes allows us to do something that has seldom been possible in previous studies [50] and allow recipients to construct their own learning by means of close interaction with peers and with the team providing the feedback [51–53].

Data collection#

Ultimately, we want to be able to present clinicians with information about thrombolysis in a way that will encourage them to change their practice and improve patient outcomes. Understanding how and what clinicians think when we introduce that information will help us to optimise the way we do it. To attain that understanding we will use an iterative combination of two methods: think-aloud interviews and co-production workshops.

Think-aloud interviews are a form of cognitive interviewing that involve inviting participants to give voice to their thoughts as they respond to something in front of them [54]. They help us understand thought processes and have been widely used in the development and evaluation of health technologies [55]. We will use this approach to collect and understand the responses of individual clinicians to the information with which we present them and will feed this into our workshops. While remaining flexible to project needs, we will focus interviews especially on two areas we consider most significant: 1) use of artificial clinical vignettes (which seek to show and explore differences in clinical decision-making), and 2) trust in the models.

Co-production workshops are useful for our purposes because the ways in which people, including clinicians, interpret and make sense of information relating to their practice has both individual and social components [56,57] and professional interactions influence decisions regarding thrombolysis [43]. Studying the processes by which this interpretation occurs can be difficult and time consuming (Gabbay and Le May [58] spent years observing General Practitioners) but through these workshops we hope to arrive at an approximation of some of the group processes involved. At the same time, these workshops will be where participants can propose and discuss changes to our intervention, which we will then show to participants in our interviews. We will use these workshops to present and gain feedback on both the content and form of the key output of the SAMueL-2 models.

By alternating between information gathering (through interviews) and intervention refinement (in workshops) we will incrementally modify and improve the style and substance of our intervention. We will repeat interviews with the same clinicians as well as engage new interviewees at each iteration. By using a panel approach, with two groups of stakeholders (clinicians plus PPI representatives plus other stakeholders such as managers) each convened at three-month interviews, we will engage group members as co-producers of our model-based intervention. To us, this means that we will go beyond having clinicians and others as informants and will share power over decision-making and information-sharing with them in a way that enables joint ownership, understanding, and support for both the process and the outcomes, along the lines proposed by NHS England, NHS Improvement, and the Coalition for Personalised Care (C4CC 2020).

Recruitment#

To enable us to explore why low thrombolysis rates persist in some acute stroke services we will ensure we engage clinicians (medics and specialist stroke nurses) working in these services, along with non-clinical staff involved in the commissioning of services. Our previous research for SAMueL-1 identified that R&D departments in low thrombolysing sites (often smaller, more rural, more socio-economically deprived) have lower capacity and capability to participate in qualitative studies (which are perceived as low priority), and can struggle to identify a physician as local principal investigator. Working with our NIHR CRN Research Delivery Manager and NIHR Study Support Service Manager, our recruitment strategy will involve a CRN nurse actively engaging the sites (especially ensuring we have good representation from those that are in the lower tertile for thrombolysis in the SSNAP audit), conducting site initiation visits, and supporting local capacity and capability to engage and recruit acute stroke clinicians.

In SAMueL-1 we also recognised that physicians who thrombolyse less are also less likely to engage with us through existing stroke networks and conferences. To address this, we will work with the new ISDNs – whose remit is specifically to improve the whole stroke pathway by facilitating a collaborative approach to service transformation – as an additional way of identifying and engaging clinicians. Where we identify local and less formal networks we may use snowballing techniques, asking participants to identify suitable peers and colleagues whom we can then approach to participate. Health Research Authority (HRA) ethical approval will be required for this proposal and we will ensure that all recruitment practices are compliant.

We aim to recruit 40 clinicians in total, and in order to be flexible and minimise any burden, we will offer them the opportunity to participate in an interview (individual or as part of a local group) and/or participate in our stakeholder workshops. As an additional incentive to participate, we will offer them a £40 voucher for each episode of engagement, which will include the option of charity donation (such as to Médecins Sans Frontières).

Data analysis#

Building on our SAMueL-1 qualitative work, we will undertake a Framework Analysis [59,60] of the interview and workshop data as well as of our field-notes and demographic data about the stroke delivery networks. All data will be transcribed, anonymised and managed in NVivo. Our analysis will be informed by the NASSS framework, specifically for exploring the complex configuration of conditions in which technological innovations may flourish or fail [61]. This will enable exploration of factors such as our stakeholders’ perceptions of and attitudes to stroke service delivery, machine learning, the modelling ‘offer’, interpersonal dynamics, organisational capacity to innovate (both local and central), as well as the broader cultural context of resilience and scope for adaptation. This will maximise the clinical application of our research findings and enhance the development of the modelling outputs to support staff working with stroke patients to enhance their thrombolysis decision making.

Sampling#

The data used in this work is historic anonymised national audit data from SSNAP. We use all emergency stroke admissions in SSNAP (three years data), though we restrict the modelling to hospitals classed by SSNAP as ‘routinely admitting teams’ with at least 100 emergency stroke admissions per year. For qualitative research we will allocate hospitals to tertile of thrombolysis use and sample evenly from each.

Anticipated route to impact#

The ultimate aim of the project is to assist SSNAP in improving use of thrombolysis. Clinical expert opinion is that there is currently predominantly under-use of thrombolysis, but the project is open-minded to the possibility that some units may have over-use of thrombolysis. As we are working through SSNAP, the focus will be on producing tools that provide rich analysis at national, regional (Integrated Stroke Delivery Networks, ISDNs), and hospital level. We will use the Qualitative Research arm of the project to extend and refine the analysis performed, but key example of anticipated output include:

We will petition NHS-England to include the principle of the use of local targets for thrombolysis in the NHS Long Term Plan.

The SSNAP audit will provide hospital thrombolysis targets for each hospitals. The effect on thrombolysis and anticipated outcomes of changes to pathway speed (including ambulance response times), determination of stroke onset, and effect of changing clinical decision-making will be provided for each hospital. This will also be collated for ISDNS.

A one-off analysis of organisation factors on thrombolysis use and speed will be provided to ISDNs.

An analysis of patient characteristics where decision-making differs between hospitals will be provided to ISDNs. A preliminary analysis suggests that factors that make decisions more variable between hospitals, compared to patients where the large majority of hospitals would agree to give thrombolysis include: 1) having an estimated, rather than precise, onset time, 2) arrive later and/or scanned later after arrival, 3) have a lower NIHSS, 4) have greater disability before stroke, 5) do not have facial palsy or visual field deficits. This preliminary analysis was conducted after writing up the SAMueL report, but is available at: https://samuel-book.github.io/samuel-1/random_forest/characterise_contentious_patients.html

There is potential to highlight to hospitals patients where the model predicted high probability of receiving thrombolysis, but the patient did not receive thrombolysis. This may be due to missing factors in the SSNAP data, but may also highlight patients where the thrombolysis pathway could have failed.

Summary of patients/service users/carers/public as research participants#

The data used in this work is solely historic anonymised national audit data from SSNAP. We do not recruit any patients/service users/carers/public as research participants.

Leon Farmer, a PPI representative is a co-investigator on the project and will join all project meetings.

A PPI group will meet nine times throughout the course of the project. Key roles of the PPI group are:

To provide a lay audience for helping the project to refine communication of aims, methods and results (this has previously been extremely useful, and led to new summary visualisations of the research).

Allow a lay audience to interrogate the study methods and findings from a different perspective from the project team, and help direct research as appropriate. Previous experience is that in preparing research findings for the PPI group, the most important outputs of the project have become clearer. The PPI group will be used as a sounding board for investigating potential bias in the model…

Assist the project team in producing plain English project outputs.

Dissemination, outputs, and anticipated Impact#

What do you intend to produce from your research?#

Practical output – the SAMueL tool (code) to be run as part of national stroke audit#

The key practical output is to produce code that can be run as part of ‘business as usual’ for the national stroke audit SSNAP, to create sophisticated audit outputs on use of thrombolysis. During our first project we have ensured that all code developed may be run using open source libraries, and have made the code compatible with raw SSNAP query output. SAMueL-1 code is being piloted by SSNAP in August 2021.

At a national level we plan to produce high level outputs that can be incorporated into active dashboards (using the same streamlit.io framework SSNAP is adopting) and quarterly and annual stroke audit reports:

Bespoke hospital-level thrombolysis targets that take local patient population characteristics into account.

Identification of the key drivers for improving thrombolysis use at each hospital (or conversely, a warning that thrombolysis use appears to be unusually higher than expected): these will be a hierarchy of the impact of: 1) speeding the pre-hospital pathway, 2) speeding the hospital pathway, 3) increasing the proportion of stroke patients with determined stroke onset time, 4) modified decision-making guided by ‘benchmark’ hospitals and their ‘similar cluster’ (similar patient population).

What are the expected thrombolysis-related outcomes at each hospital, including adverse effects at current use and optimised ‘target’ use, with attendant health economic outcomes.

We will develop more detailed outputs for local (hospital) or regional network (e.g. ISDN) level. The exact content of those will be decided by the output of the modelling and the feedback we receive during the qualitative work, but examples could be:

Web-based interactive dashboards using streamlit.io as being adopted by SSNAP.

Regional-level (e.g. ISDN) reports summarising outputs for hospitals within the network. This may include, for example, synthetic clinical vignettes of patients that illustrate differences in decision-making between hospitals.

Hospital-level reports detailing more analysis, and showing comparisons with other hospitals (e.g. hospitals with similar demographic, or other hospitals within the ISDN).

Patient-facing outputs (developed with our PPI group).

Knowledge#

In addition to incorporating the SAMueL-2 tool into routine national audit outputs we expect to have three main areas of knowledge output:

Improved understanding of the causes of inter-hospital variation in use of thrombolysis (and a framework for thrombectomy), along with the effect of key process changes that may affect thrombolysis use. This will extend our current work by including additional inputs (pre-hospital pathway, and hospital organisation factors), and additional outputs (prediction of likely outcome at patient level, health economic outcomes).

Improved understanding of the application of advanced modelling and machine-level tools to national audit, including production of synthetic data and artificial patient vignettes. We plan to significantly extend our work on the explainability of the model, and individual model predictions, along with an in-depth study of potential biases in these types of models. We hope these findings can also be adapted to other national audits and we will explore that potential with HQIP.

Improved understanding of how clinicians interact with these advanced audit tools, especially focusing on the hospitals/clinicians who may feel most challenged by the outputs, and how to frame results to be seen as most constructive and supportive of clinical practice change.

Knowledge dissemination will be via:

NIHR Journals Library report

Engaging with ISDNs.

Engaging with HQIP to share approach and results with the other 27 national audits (see https://www.hqip.org.uk/a-z-of-nca/).

Selected papers (e.g. using free and open science platforms like medRxiv and Open Science Foundation).

Attendance at target conferences such as UK Stroke Forum, and European Stroke Organisation.

Links to project material from SSNAP on the publicly accessible strokeaudit.org website and the SSNAP Twitter account, supported by webinars (SSNAP already run a regular schedule of these).

Project website and online book.

Informal social media content: YouTube summaries, Tweets, podcasts.

Appropriate links with the NIHR Centre for Engagement and Dissemination to pursue further specific routes to dissemination/impact.

What further funding or support will be required if this research is successful?#

The project most importantly needs continued support from the national stroke audit, SSNAP. The code from the project is designed to run simply alongside the regular SSNAP dashboards and quarterly/yearly outputs, and will using the same frameworks (Python backend and streamlit.io dashboards). The overall aims of the project are also dependent on the continuance of the quality improvement effort in stroke currently manifested in the ISDNs.

Assuming the project is successful, we would also like to collaborate with HQIP to look at what other national audits may benefit from this type of approach.

What do you think the impact of your research will be and for whom?#

Ultimately the key impact should be for patients – helping to make emergency stroke care more consistent between hospitals so that a patient receives similar care wherever they are admitted. We will also help inform clinicians, commissioners, and other stakeholders on what additional interventions would lead to better emergency stroke care. Patient advocacy groups such as the Stroke Association remain very concerned about the unusually high and persistent degree of variation in thrombolysis practice across the UK at a level that would be considered intolerable in other areas of clinical practice – in essence, a ‘postcode lottery’. Implementation of our findings would reassure policymakers, people with stroke and the public that the NHS is committed to reducing unwarranted variation and consistently delivering evidence-based, NICE-approved therapies for emergency stroke.

Project / research timetable#

Pre-work (-3 to 0 months)

HQIP data access request for SSNAP data. This period also to include a discussion with HQIP on the approval process for sharing of synthetic data (previous discussions were indicated that this would be a follow-on request after synthetic data had been generated). Begin recruitment of research fellow when possible.

0-6 months

Modelling: 1) obtain data, 2) create pathway models, 3) create first machine learning models, 4) create synthetic data for sharing, 5) verify health economics sources.

Qualitative: 1) recruit research fellow, 2) identify sites, 3) complete HRA submission and approval process, 4) begin recruitment of participants/ collaborators.

Milestone 6 months: first models are ready to share. Synthetic data ready for HQIP request to share. We will initially share just hospital-level modelling. After HQIP approve sharing of synthetic patient data we will use synthetic patient vignettes to exemplify our early findings.

6-12 months

Modelling: 1) add in health economics model, 2) Add in explanatory methods (to explain model overall, and to explain individual decisions), focusing on Shapley values, 3) Continue to refine models and outputs in conjunction with qualitative workstream.

Qualitative: 1) continue recruiting participants/ collaborators, 2) Commence data collection through focus groups and individual conversations.

Milestone 12 months: First code to share with SSNAP produced.

12-18 months

Modelling: continue to refine models and outputs iteratively in conjunction with qualitative workstream, 2) detailed analysis of potential biases in model; 3) testing of code in collaboration with SSNAP analysts, 4) pilot work on thrombectomy.

Qualitative: 1) continue data collection, 2) begin framework analysis of qualitative data.

Milestone 18 months: Second code to share with SSNAP produced.

18-24 months

Modelling: 1) project write up and documentation including production of Jupyter Book of code, synthetic data, and results, 2) start dissemination activities.

Qualitative: 1) complete data collection and analysis, 2) write up and disseminate qualitative findings, 3) start dissemination activities.

Project management#

The project has an experienced project planner, Chrissie Walker, on the project team.

The project will be informed by an external advisory committee. This will continue from the current project chaired by Dr Ajay Bhalla (SSNAP audit associate director, and clinical lead for stroke at Guy’s and St Thomas’), with other members including Prof Gary Ford CBE (Chief Executive Officer of Oxford Academic Health Science Network and Chair of the AHSN Network, Professor of Stroke Medicine, and Visiting Professor of Clinical Pharmacology, Oxford University) and one other (currently being recruited after a retirement of previous member). The external advisory committee will meet four times throughout the project (approx. at months 0, 9, 15, and 22).

The project will have inclusive project team meetings every 2 months, involving all team members. All key project-level decisions are expected to be made at these meetings.

The project will have an internal steering group (Martin James, Michael Allen, Ken Stein, Iain Lang) who will review progress every 4 months (or ad-hoc as required) and highlight issues for resolution to the project team.

Ethics / Regulatory Approvals#

SSNAP audit data will be accessed through prescribed access protocols managed by HQIP (the team has experience of this from SAMueL-1). We will work with HQIP on a two-stage process: 1) accessing data for internal project use, and 2) gaining approval to be able to share synthetic patient-level data. For qualitative research we will seek ethical approval from the University of Exeter College of Medicine and Health REC, followed by a HRA. Once HRA approval is in place then site level approval from the selected NHS sites will be sought in collaboration with the NIHR relevant Clinical Research Networks (this would be an automatically-adopted study).

The project has a broad range of expertise competent in all areas of the project.

Clinical and Academic: Prof Martin James is co-lead for SAMueL-2. He is the stroke lead for Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital and Clinical Lead for the SW Peninsula ISDN, and has over 30 years of experience of applied health research in the aetiology of stroke, stroke prevention, and quality improvement, and as chief investigator of randomised controlled trials. Since 2019 he has been the Clinical Director of the national stroke audit (SSNAP). He is influential at a national level, for example co-authoring the Royal College of Physicians 2016 National Clinical Guideline for Stroke. Martin will be supported by Prof Ken Stein. Ken is highly experienced public health physician and applied healthcare researcher, with extensive experience in health technology assessment and evidence synthesis, and he is currently Editor in Chief of the NIHR Journals Library.

Modelling and Machine Learning: Dr Michael Allen is co-lead for SAMueL-2, and is a very experienced researcher and practitioner of applied healthcare modelling, using modelling based on clinical pathway simulation, machine learning, and geographic optimisation methods. His modelling of acute stroke services has been commissioned by NHS England, NHS Scotland, NHS Wales, HSC Northern Ireland, and regional NHS commissioners. Dr Allen has also published pilot work on patient-level synthetic data generation. Dr Allen is supported by Prof Richard Everson, Professor of Machine Learning at the University of Exeter, , a Fellow of the Alan Turing Institute and Director of the Institute for Data Science & AI. The modelling team also includes two experienced modelling and machine learning researchers who were part of SAMueL-1: Dr Charlotte James and Kerry Pearn.

Qualitative research: The qualitative research is led by two experienced qualitative researchers: Dr Iain Lang, and Dr Julia Frost. Dr Lang’s research focus is on implementation research, knowledge mobilization, and implementation science, particularly in relation to health and care in later life. Dr Frost is qualitative lead on several NIHR-funded studies and leads the Third Gap Research Group at the University of Exeter. Dr Lang and Dr Frost are supported by Prof Catherine Pope, professor of medical sociology at the University of Oxford. Prof Pope is an internationally recognised researcher and expert in qualitative and mixed methods for applied health research.

Health Economics: The health economics part of the project is led by Prof Peter McMeekin, Northumbria University. Prof McMeekin has extensive experience in applying health economic analysis to stroke outcomes, and has been/is lead for health economics evaluation in stroke for a number of NIHR projects/programmes: PASTA, PEARS, OPTMIST. Prof McMeekin will help transfer the models developed in those other programmes to SAMueL-2, with implementation being performed by the modelling and machine learning group (see above). He will also use SAMueL-2 as an opportunity to further develop health economics models in stroke.

PPI lead#

The project team has a PPI member as co-applicant, Mr Leon Farmer. Mr Farmer is a stroke survivor, and played a key PPI role in SAMueL-1 although not in a formal role as a co-applicant. Leon is keen and ready to take a larger role in this new project, and in this he will be supported by Dr Kristin Liabo, the lead of the Patient and Public Involvement group in the NIHR South West Peninsula ARC (PenARC).

Success criteria and barriers to proposed work#

Success criteria#

Ultimately the project will be a success if it contributes to improved stroke outcomes through the better use of thrombolysis. However, it is well recognised that audit has greater impact when interventions are multi-faceted, get the right message to the right recipients, considers the needs of clinicians and patients, and emphasises action towards realistic goals over measurement. Our project aims to increase the precision of feedback from national audit, and therefore contribute to the broader range of quality improvement initiatives to increase the population benefit from acute stroke treatments.

More practical success criteria would be:

Implementation of project outputs (the SAMueL-2 tool) as part of routine audit by SSNAP.

Positive feedback received during qualitative research interviews, including examples of increased ‘willingness to change’ on the basis of receiving this enhanced audit output.

Interest from other audits on application in other clinical domains.

Barriers to proposed work#

Risk of not accessing SSNAP data, or being unable to share synthetic patient-level data: As the project team has previously accessed SSNAP data the risk of not accessing data appears minimal, though requesting more data may lead to some extra time needed to negotiate regulatory processes. There is also some risk about being unable to share synthetic patient-level data. HQIP have previously been encouraging on the production of synthetic data, and have informed us that when produced we should return to HQIP with the request to share. We have mitigated this risk by performing some early pilot work in which we demonstrated the ability to produce synthetic patient level data with enough quality to train machine learning models well. We will mitigate both of the above risks by starting the data access process three months before the planned project start.

Risk of not recruiting sufficient clinicians or other stakeholders into qualitative research: Our experience from SAMueL-1 was that it is not difficult to access senior stroke clinicians from large departments with higher thrombolysis use. More challenging was to access those from smaller departments, or from departments with lower thrombolysis use, or more general physicians responsible for delivering thrombolysis. In order to mitigate this risk we are modifying our approach to improve our reach to the latter groups, and we have significantly increased resource for qualitative work compared with SAMueL-1, to allow for the significant time and effort required to engage clinicians from this group and build relationships. Compared with our previous work, we are also seeking to establish a project-long relationship with these clinicians. We are establishing a formal relationship with CRNs to aid recruitment (which has been costed into the project) and will offer an incentive for all interviews/workshops in the project (through vouchers or charity donations). We will also be flexible to how people want to interact with us – using both focus groups (workshops) or individual conversations as preferred. We will also make more background available in short YouTube videos.

Risk of models not being implemented: The final risk is that we produce a model that is not implemented by SSNAP. We believe this risk is well-mitigated by having the clinical director of the SSNAP as co-lead, and another associate director of SSNAP on the external advisory committee. The project also has established links with the database/software team of SSNAP, to ensure that we overcome minimal technical barriers to implementation. Implementation is also aided by support from the National Clinical Director of Stroke at NHS England.

References#

NIH National Heart Blood and Lung Institute. Stroke [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/stroke

Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, Mensah GA, Connor M, Bennett DA, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2014 Apr 13;383(9913):245–55.

HQIP. Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme - Annual Report 2019-20. HQIP. 2021.

Newton JN, Briggs ADM, Murray CJL, Dicker D, Foreman KJ, Wang H, et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386(10010):2257–74.

Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. The Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1929–35.

Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, De Marchis GM, Fonseca AC, Padiglioni C, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. European stroke journal. 2021 Mar 1;6(1):I–LXII.

Norrving B, Barrick J, Davalos A, Dichgans M, Cordonnier C, Guekht A, et al. Action Plan for Stroke in Europe 2018–2030. European Stroke Journal. 2018;3(4):309–36.

Bray BD, Campbell J, Cloud GC, Hoffman A, Tyrrell PJ, Wolfe CDAA, et al. Bigger, faster?: Associations between hospital thrombolysis volume and speed of thrombolysis administration in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3129–35.

Lahr MMH, Luijckx GJ, Vroomen PCAJ, Van Der Zee DJ, Buskens E. Proportion of patients treated with thrombolysis in a centralized versus a decentralized acute stroke care setting. Stroke. 2012;43(5):1336–40.

Bembenek J, Kobayashi A, Sandercock P, Czlonkowska A. How many patients might receive thrombolytic therapy in the light of the ECASS-3 and IST-3 data? International Journal of Stroke. 2010;5:430–1.

NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019.

NHS England and NHS Improvement. National Stroke Service Model: Integrated Stroke Delivery Networks. 2021.

Meretoja A, Strbian D, Mustanoja S, Tatlisumak T, Lindsberg PJ, Kaste M. Reducing in-hospital delay to 20 minutes in stroke thrombolysis. Neurology. 2012;79(4):306–13.

Meretoja A, Weir L, Ugalde M, Yassi N, Yan B, Hand P, et al. Helsinki model cut stroke thrombolysis delays to 25 minutes in Melbourne in only 4 months. Neurology. 2013 Sep 17;81(12):1071–6.

NHS. Clinical Audit [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/clinaudit/

SSNAP. Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.strokeaudit.org/

Foy R, Skrypak M, Alderson S, Ivers NM, McInerney B, Stoddart J, et al. Revitalising audit and feedback to improve patient care. The BMJ. 2020 Feb 27;368.