Definitions for stroke#

work in progress

Stroke types#

The methodology described here is for patients with an ischaemic stroke. Ischaemic stroke is a stroke caused by the blockage of blood supply to an area of the brain, caused by a clot.

These patients can be further defined by the location of the clot:

those with a large vessel occlusion (LVO);

and those not with a large vessel occlusion (nLVO).

Ischaemic strokes account for 80-85% of all strokes, with the remainder being haemorrhagic strokes where loss of blood supply is caused by a bleed in the brain.

To select the relevant patients for each cohort we will use the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on arrival as a surrogate to classify patients as nLVO (NIHSS 0-10) or LVO (NIHSS 11+).

Late-presenting patients#

Note: the time to no effect from Fransen et al. did not include those patients who may be selected for late treatment based on advanced imaging. In this method we do not include late-presenting patients in our outcome modelling.

Treatments#

Reperfusion describes the restoration of blood flow following an ischaemic stroke. There are two potential reperfusion treatments:

Thrombolysis (also known as as intravenous thrombolysis, IVT) is a medical therapy where clot-busting drugs are used to reduce or remove the blood clot. About 20% of all stroke patients are suitable for thrombolysis.

Thrombectomy (also known as mechanical thrombectomy, MT) is the physical removal of a clot, by a mesh device under image guidance. Thrombectomy is suitable only for clots in a large vessel (these generally cause the worst strokes), and is a suitable treatment in about 10% of all stroke patients.

Patients with an nLVO can be treated with IVT.

Patients with an LVO can be treated with IVT and/or MT.

Note:

In Goyal’s metanalysis of MT, 85.1% of patients in the trial had also received IVT. The trial results therefore mostly reflect IVT/MT vs MT alone. If patients first attend an IVT-only centre, then it is possible that if they respond well to IVT they will not proceed to MT (they are, arguably, more likely to proceed to MT when IVT and MT are more tightly coupled in time). The overall benefit in LVO patients is likely to a conditional sum of IVT and MT benefit - that is patients may first benefit from IVT, and those patients who do not respond well to IVT may benefit from additional MT. Currently in the UK 52% of patients are admitted directly to an MT-capable centre (Phil White, private communication).

Time delay#

Reperfusion treatment becomes less effective with increasing time after stroke (with the loss of effect occurring over some hours). Each treatment has no effect after a specified duration (6.3 hours for IVT, and 8 hours for MT).

In other words, the sooner a patient recieves reperfusion treatment, the fewer stroke related disabilities they could end up with.

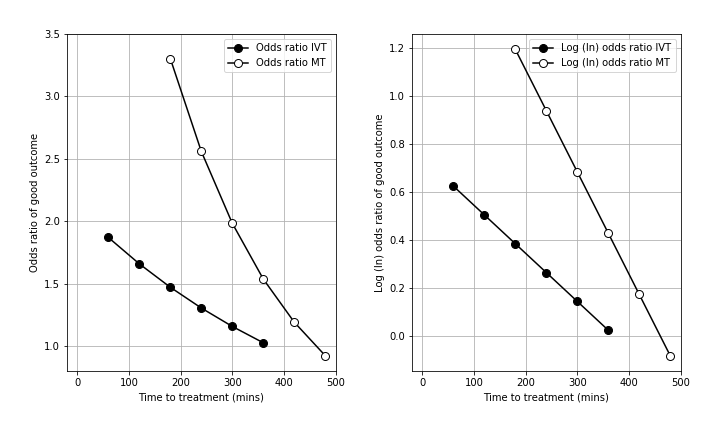

The deacy in effectiveness of reperfusion is shown in the figure below (left panel = odds ratio, right panel = log odds ratio, IVT = thrombolysis, MT = thrombectomy).

In order to estimate these two mRS distributions, we use data from reperfusion treatment clinical trials and stroke admission data from England and Wales.

The t = 0 mRS distributions are calculated to give the expected mRS distributions if treatment was given immediately after stroke onset, and also include the risk of excess deaths caused by taking the treatment.

The t = No Effect mRS distributions are based on mRS distribution data when patients did not receive any treatment (this represents what will happen if the patient takes the treatment at t = No Effect).

Outcome measures#

Disability levels may be measured in various ways. In this project we are using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). It is a commonly used scale for measuring the degree of disability or dependence in the daily activities of people who have suffered a stroke or other causes of neurological disability [Saver et al., 2010].

The scale runs from 0-6, running from perfect health without symptoms to death:

Score |

Description |

|---|---|

0 |

No symptoms. |

1 |

No significant disability. Able to carry out all usual activities, despite some symptoms. |

2 |

Slight disability. Able to look after own affairs without assistance, but unable to carry out all previous activities. |

3 |

Moderate disability. Requires some help, but able to walk unassisted. |

4 |

Moderately severe disability. Unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance, and unable to walk unassisted. |

5 |

Severe disability. Requires constant nursing care and attention, bedridden, incontinent. |

6 |

Dead. |

Note: From this point onwards we will refer to disability distributions as mRS distributions.

In addition to mRS, we may calculate utility-weighted mRS (UW-mRS). UW-mRS incorporates both treatment effect and patient perceived quality of life as a single outcome measure for stroke trials.

The default utility scores used in the model are based on a pooled analysis of 20,000+ patients, from Wang et al (2020). The Utilities for each mRS level are shown below.

mRS Score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Utility |

0.97 |

0.88 |

0.74 |

0.55 |

0.20 |

-0.19 |

0.00 |

“Good” outcomes#

Emberson et al. and Fransen et al. have described the declining effect as the declining odds ratio of achieving an essentially ‘good outcome’ following thrombolysis (Emberson) or thrombectomy (Fransen). A ‘good outcome’ has been described differently with studied on thrombolysis generally using a threshold of mRS 0-1 at 3-6 months, and thrombectomy studies generally using a threshold of mRS 0-2 at 3-6 months. The odds ratio describes the odds of a ‘good outcome’ relative to the odds of a ‘good outcome’ in an untreated control group.

Resulting mRS distributions#

This method calculates disability outcome distribution estimates for three patient-treatment cohorts:

nLVO-IVT (patients with an nLVO that are treated with IVT)

LVO-IVT (patients with an LVO that are treated with IVT)

LVO-MT (patients with an LVO that are treated with MT).

two time stages: 1) receiving reperfusion treatment as soon as their stroke began (this will be referred to as time of stroke onset, and we will use the terminology “t = 0”), and 2) receiving reperfusion treatment at the duration after stroke onset where the treatment has no effect (this will be referred to as time of no effect, and we will use the terminology “t = No Effect”).

For each patient-treatment cohort, we estimate two mRS distributions:

mRS distribution if treatment is given at t = 0 (time of stroke onset),

mRS distribution if treatment is given at t = No Effect (time of no effect).

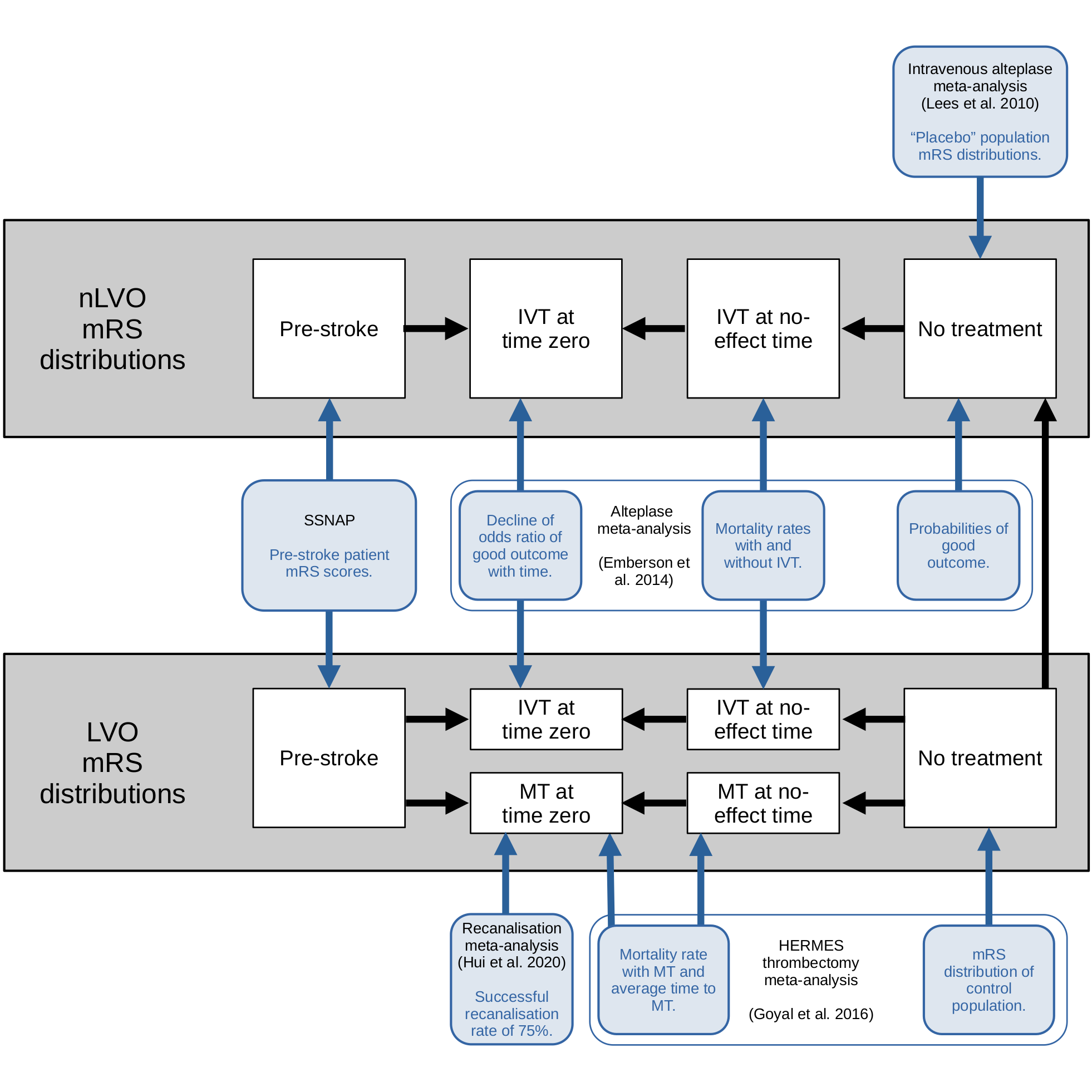

The method is built by synthesising data from multiple sources figure 1, including reperfusion treatment clinical trials and 3 years’ worth of stroke admission data for England and Wales. The details are given on the LINK ME”” page.

The following graphic shows which data sources are used in each step of the mRS distribution derivations:

Fig. 2 Flowchart of the use of multiple data sources in a disability-level model#

We can then use interpolation to determine the disability distribution at any point inbetween.

The resulting mRS distributions are shown in the following image.

TO DO: find the image

References used in modelling#

de la Ossa Herrero N, Carrera D, Gorchs M, Querol M, Millán M, Gomis M, et al. Design and Validation of a Prehospital Stroke Scale to Predict Large Arterial Occlusion The Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation Scale. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013 Nov 26;45.

Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. The Lancet 2014;384:1929–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5

Fransen, P., Berkhemer, O., Lingsma, H. et al. Time to Reperfusion and Treatment Effect for Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Feb 1;73(2):190–6. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3886

Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet 2016;387:1723-1731. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X

Hui W, Wu C, Zhao W, Sun H, Hao J, Liang H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Recanalization Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke With Large Vessel Occlusion. Stroke. 2020 Jul;51(7):2026–35.

IST-3 collaborative group, Sandercock P, Wardlaw JM, Lindley RI, Dennis M, Cohen G, et al. The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 379:2352-63.

Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. The Lancet 2010;375:1695-703. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6

McMeekin P, White P, James MA, Price CI, Flynn D, Ford GA. Estimating the number of UK stroke patients eligible for endovascular thrombectomy. European Stroke Journal. 2017;2:319–26.

SAMueL-1 data on mRS before stroke (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.6896710): https://samuel-book.github.io/samuel-1/descriptive\_stats/08\_prestroke\_mrs.html{.uri}

Wang X, Moullaali TJ, Li Q, Berge E, Robinson TG, Lindley R, et al. Utility-Weighted Modified Rankin Scale Scores for the Assessment of Stroke Outcome. Stroke. 2020 Aug 1;51(8):2411-7.

Saver JL, Filip B, Hamilton S, et al. Improving the Reliability of Stroke Disability Grading in Clinical Trials and Clinical Practice. Stroke 2010;41:992–5. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571364